In an expected but unfortunate development for investors, Motor Oil was dropped from the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) Greece large cap index in the early hours of the morning.

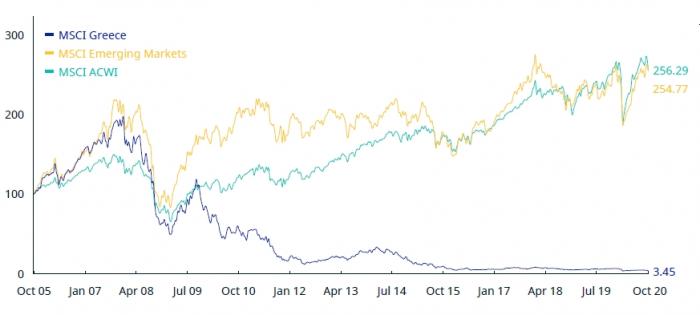

Through the adventurous history of Greece’s participation in the MSCI indices, the initially promising - and subsequently disappointing - course of the ATHEX is written out with great clarity, as the Greek MSCI has yielded only 3.5% since 2005, while profits from the two key MSCI indices exceed 250%.

Motor Oil's exit from the Greek MSCI large cap index, with a transition to the low capitalization index was predicted based on the numbers. When it joined the index, in August 2018, the group’s capitalization exceeded 2 billion euros, while now it has been reduced by half, to about 1 billion euros. The exit from the index is estimated to cost the share net outflows from passive funds (index funds) of about 30 million euros.

It is noted that for MSCI the main criterion for adding shares to its indices is the free float of shares, those that are not controlled by the main shareholder. It is clarified that there is no fixed reference limit to judge whether a stock is included in the high or low capitalization index, but this constantly changes depending on the performance of stock markets (when they rise, the limits increase).

The MSCI avoided replacing Motor Oil with another stock in this revision, which takes effect later this month, although many analysts argue that Mytilineos' market capitalization would justify its listing in the large cap index. Thus, the Greek market is represented by only three shares in the large cap index: OTE, OPAP and Jumbo. Three shares is the minimum set by MSCI for the formation of a local index. The only share favored by this revision was that of ELPE, which was included in the small capitalization index, taking the place of HELEX.

The case of Greece is perhaps the worst example of a stock market failing that is monitored by MSCI. In June 2013, the Athens Stock Exchange became the first and only one in the history of MSCI (since 1987), which was downgraded from the developed market category to that of emerging market. Downward revisions of other countries have also taken place, of course, in other cases as well, but only in the case of Greece was the revision recorded from the top tier of developed countries.

The MSCI had then stressed that the ATHEX did not meet the basic criteria to participate in developed markets, as for two years its capitalization had fallen below the minimum while it had not followed the progress made by other markets in improving trading practices. Behind all this, of course, was the most serious issue: that the country was fighting to stay in the eurozone, in a battle which continued for several more years.

One could hardly have predicted this failure in May 2001, when Greece switched from the MSCI emerging market index to the playing field of developed markets, securing the privilege of access to huge investment funds. At that time, Greece was living the miracle of entering the monetary union of Europe and everyone was anticipating that the ATHEX could stand with dignity next to the developed markets.

MSCI data show very clearly how the ATHEX disappointed the international investment community. As shown in the graph, MSCI Greece from October 2005 until the beginning of 2010, when the country was on the verge of bankruptcy, there was a high degree of correlation with the global index - MSCI flagship, the ACWI, but also the emerging index markets, MSCI Emerging Markets.

The country’s fiscal and economic collapse, which brought it close to exiting the eurozone, dramatically separated the course of the Greek MSCI from the other two indices, which followed an upward course, while the Greek index slid constantly lower.

Cumulative performance of the MSCI Greece index

The annual returns of the period 2006-2020 are also interesting, especially if one correlates them with the economic and political events of the period. 2006 was the only year before the crisis, where the Greek market outperformed the indices of developed and emerging markets. The crisis of 2008 showed, however, that the then government's theories of a "fortified" economy had little to do with reality. It turned out that the stock market was completely exposed and fell 66%, much more than the developed and emerging peers.

2010 proved to be a catastrophic year, when the battle to avoid a general economic collapse began, but also in 2015, when negotiations with the Europeans brought the country close to exiting the euro. These two years, as well as in 2008, brought negative returns that exceeded 60% for foreign investors who follow the MSCI indices. The first year that perhaps marked the exit from this adventure was in 2019, when with a yield of 43% MSCI Greece surpassed the two main MSCI indicators. This was followed, however, by the pandemic that separated the Greece MSCI index again this year, from the other two indices.

NONTAS CHALDOUPIS