The Economist's data on the performance of the Greek stock market and 34 other countries, included in the British magazine's survey of the best performing economies, was revealing: in 2023, the Athens Stock Exchange played in its own unique category, with a chaotic performance gap from other international markets. Many investors are beginning to wonder whether, after such a rally, Greek stocks are overvalued.

The Economist named Greece, for the second year in a row, as the best-performing economy, ranking 35 mostly wealthy economies on five indicators: core inflation, inflation range, GDP, employment, inflation-adjusted stock prices. On the four indicators, Greece's performance is broadly comparable to that of other countries. In stock prices, however, Greece was the leader by a wide margin.

The Economist's list is perhaps more valuable than other comparisons of stock market returns made in nominal terms. The British magazine calculates real returns, that is, after inflation has been deducted, so that returns in countries with very high inflation, such as Turkey, and those in economies with a 'normal' level of inflation are comparable.

In this comparison, Greek equities not only rank first in terms of real return, but by almost 20 (!) points from the second market in the ranking. In 9M 2023, the real return on Greek equities was 43.8%, while in Poland it was 24.4%. Turkey, where the nominal return on equities was higher than in Greece, after deducting inflation fell to 20.6% and was fourth on the list. The best of the markets in the table had a return about half that of Greece, while there were eight countries with negative returns and 15 with single-digit returns.

The Economist comments on these performances of Greek equities with an enthusiasm that perhaps goes beyond the bounds of a conservative, financial publication. After noting that Japan's businesses are experiencing something of a renaissance and the country's stock market has had one of the best returns this year, rising in real terms by almost 20%, he points out:

- But for glorious stock returns, look thousands of miles to the west - to Greece. There the real value of the stock market has risen by over 40%. Investors have been looking anew at Greek companies as the government implements a series of pro-market reforms. Although the country is still much poorer than it was before its great collapse in the early 2010s, in a recent statement the IMF, once an enemy of Greece, praised the "digital transformation of the economy" and "increasing market competition".

- While underperforming Finns can console themselves this Christmas by drowning their sorrows in their underwear (or drunk, as is the local custom), the rest of the world should raise a glass of ouzo to this most unlikely of champions.

Because there is no bullish excess in the ASE

For many Greek retail investors, especially those with memories of the 1999 bubble and collapse, these exceptional market performances may even cause skepticism. "Could it be", is the question many are asking, "that the market has run too fast and at the first bounce will crash, leaving those investors who positioned themselves slowly with losses?"

One investor who ... knows about "bubbles" is the well-known billionaire John Paulson. Paulson made the move that made him fabulously rich before the US mortgage bubble burst, having diagnosed that the securitised loans in this category were not in fact 'A' class, but 'junk'. He invested a (small) part of the profits from that investment strategy in Greece and is now a major shareholder in Piraeus Bank.

Paulson, speaking at the Capital Link conference in New York, made it clear that not only does he not see a "bubble" in Greece, but that we are only at the beginning of a virtuous cycle that will bring more good returns:

- "It is important," he said, "that if Greeks continue to pursue pro-investment economic policies with subsequent governments, then this prosperity for Greece can extend for decades.

- In this respect, we are only at the beginning of a long-term, virtuous investment cycle. Asset values in Greece are still very attractive. Piraeus shares, for example, while up 120% this year, are still trading at just 5 times earnings and at 50% of book value"

Correcting a disaster

To see the big picture and to understand what this year's strong performance of Greek equities relative to other international markets really means, one should look back to past performance. There he will find that, in reality, the run in Greek equities this year only barely covers the lost ground created by the monumental destruction of value that took place in the Greek market during the years of the Great Crisis.

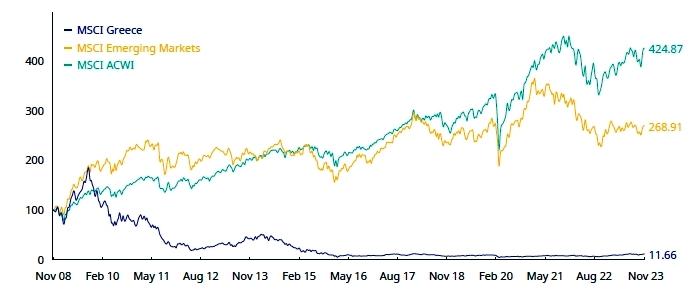

As shown in MSCI's chart, which covers the period November 2008 - November 2023, and depicts the MSCI Greece index compared to the firm's two main indices (MSCI ACWI and MSCI Emerging Markets) over this period, the Greek index almost "wiped off the map", falling from 100 to 11.66, which is mainly the result of the "break-up" of bank stocks.

In contrast, the other two indices rose significantly: the emerging market index from 100 to 269 and the developed economy index to 425. In other words, anyone who invested EUR 1,000 in Greek equities in 2008 would have EUR 116 at the end of 2023, while anyone investing in developed economies would have EUR 4,250!

All of this explains why the rise in Greek equities, which may seem frenetic and exaggerated compared to the returns of other markets, is nothing more than a move to correct the downward excesses we saw on the stock market during the crisis years. From this point of view, there seems to be no reason for anyone to be possessed by... hype by investing in Greek equities.

Valuation indices are not scary

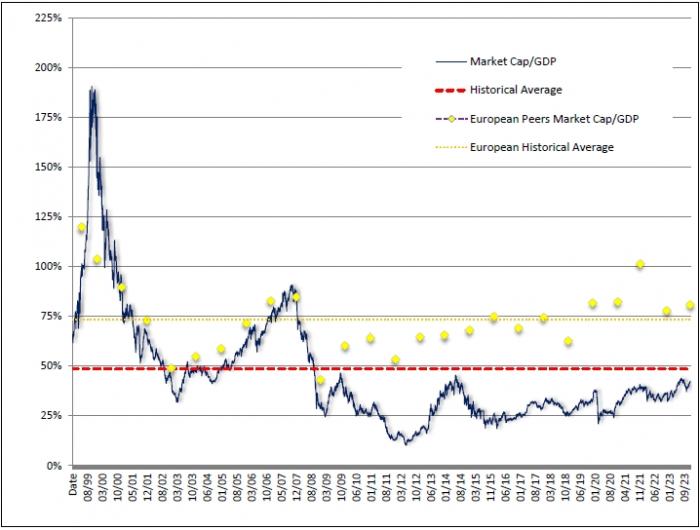

Another way of approaching the same question is through the relationship between market capitalisation, i.e. the market value of all stocks, and Gross Domestic Product - the Market Cap/GDP ratio, which is a favourite of the legendary investor, Warren Buffett.

As shown in the chart (source: Beta Financial), the real bubble can be traced back to 1999, when the Capitalization/GDP ratio had soared to over 180% in Greece, while in Europe it was around 120%. Fatefully, the collapse came which corrected the ratio of the two indices from 2000, then they converged, while from 2008 the gap started to open at the expense of Greek equities, with the largest difference being recorded in 2020.

Even after this year's rise, the Capitalisation/GDP ratio in Greece is well below 50%, when in Europe it is moving towards 80% - "a good gap to be covered by the rise in Greek equities", as Beta comments.

Other indicators used to approximate stock valuations in no way justify concerns about overvaluation. Notably, the market's P/E (price/earnings ratio) is estimated by Beta, based on this year's earnings forecasts, to be 8.1 times, compared to 7 in 2022. That is, despite the big price rise, the ratio has risen only slightly and remains in single digits, mainly because, as the brokerage explains, the return of banks to fairly high profitability comes into the equation.

The price-to-book ratio in the Greek market stands at 1.10 times and remains low, although clearly improved from the 0.60 times recorded in 2017, a value that was the lowest during the years of the crisis. The same ratio was really "salty" in 2008, the last good year before the crisis, when it reached 2.5 times.

All of this does not mean that anyone who randomly buys a stock from the Greek stock exchange board, or listens to his friend who "knows a good paper", will come out of the market with big profits. Nor is there any guarantee that for many years the market will give consistently high returns. But they do mean that there is no problem of excessive valuations in the Greek stock market. On the contrary, there is still a large enough lag relative to developed markets to justify a continued upward correction in valuations.